PostgreSQL is an awesome project and it evolves at an amazing rate. We’ll focus on evolution of fault tolerance capabilities in PostgreSQL throughout its versions with a series of blog posts. This is the fourth post of the series and we’ll talk about synchronous commit and its effects on fault tolerance and dependability of PostgreSQL.

If you would like to witness the evolution progress from the beginning, please check the first three blog posts of the series below. Each post is independent, so you don’t actually need to read one to understand another.

- Evolution of Fault Tolerance in PostgreSQL

- Evolution of Fault Tolerance in PostgreSQL: Replication Phase

- Evolution of Fault Tolerance in PostgreSQL: Time Travel

Synchronous Commit

By default, PostgreSQL implements asynchronous replication, where data is streamed out whenever convenient for the server. This can mean data loss in case of failover. It’s possible to ask Postgres to require one (or more) standbys to acknowledge replication of the data prior to commit, this is called synchronous replication (synchronous commit).

With synchronous replication, the replication delay directly affects the elapsed time of transactions on the master. With asynchronous replication, the master may continue at full speed.

Synchronous replication guarantees that data is written to at least two nodes before the user or application is told that a transaction has committed.

The user can select the commit mode of each transaction, so that it is possible to have both synchronous and asynchronous commit transactions running concurrently.

This allows flexible trade-offs between performance and certainty of transaction durability.

Configuring Synchronous Commit

For setting up synchronous replication in Postgres we need to configure synchronous_commit parameter in postgresql.conf.

The parameter specifies whether transaction commit will wait for WAL records to be written to disk before the command returns a success indication to the client. Valid values are on, remote_apply, remote_write, local, and off. We’ll discuss how things work in terms of synchronous replication when we setup synchronous_commit parameter with each of the defined values.

Let’s start with Postgres documentation (9.6):

The default, and safe, setting is on. When off, there can be a delay between when success is reported to the client and when the transaction is really guaranteed to be safe against a server crash. (The maximum delay is three times wal_writer_delay.) Unlike fsync, setting this parameter to off does not create any risk of database inconsistency: an operating system or database crash might result in some recent allegedly-committed transactions being lost, but the database state will be just the same as if those transactions had been aborted cleanly. So, turning synchronous_commit off can be a useful alternative when performance is more important than exact certainty about the durability of a transaction.

Here we understand the concept of synchronous commit, like we described at the introduction part of the post, you’re free to set up synchronous replication but if you don’t, there is always a risk of losing data. But without risk of creating database inconsistency, unlike turning fsync off – however that is a topic for another post -. Lastly, we conclude that if we need don’t want to lose any data between replication delays and want to be sure that the data is written to at least two nodes before user/application is informed the transaction has committed, we need to accept losing some performance.

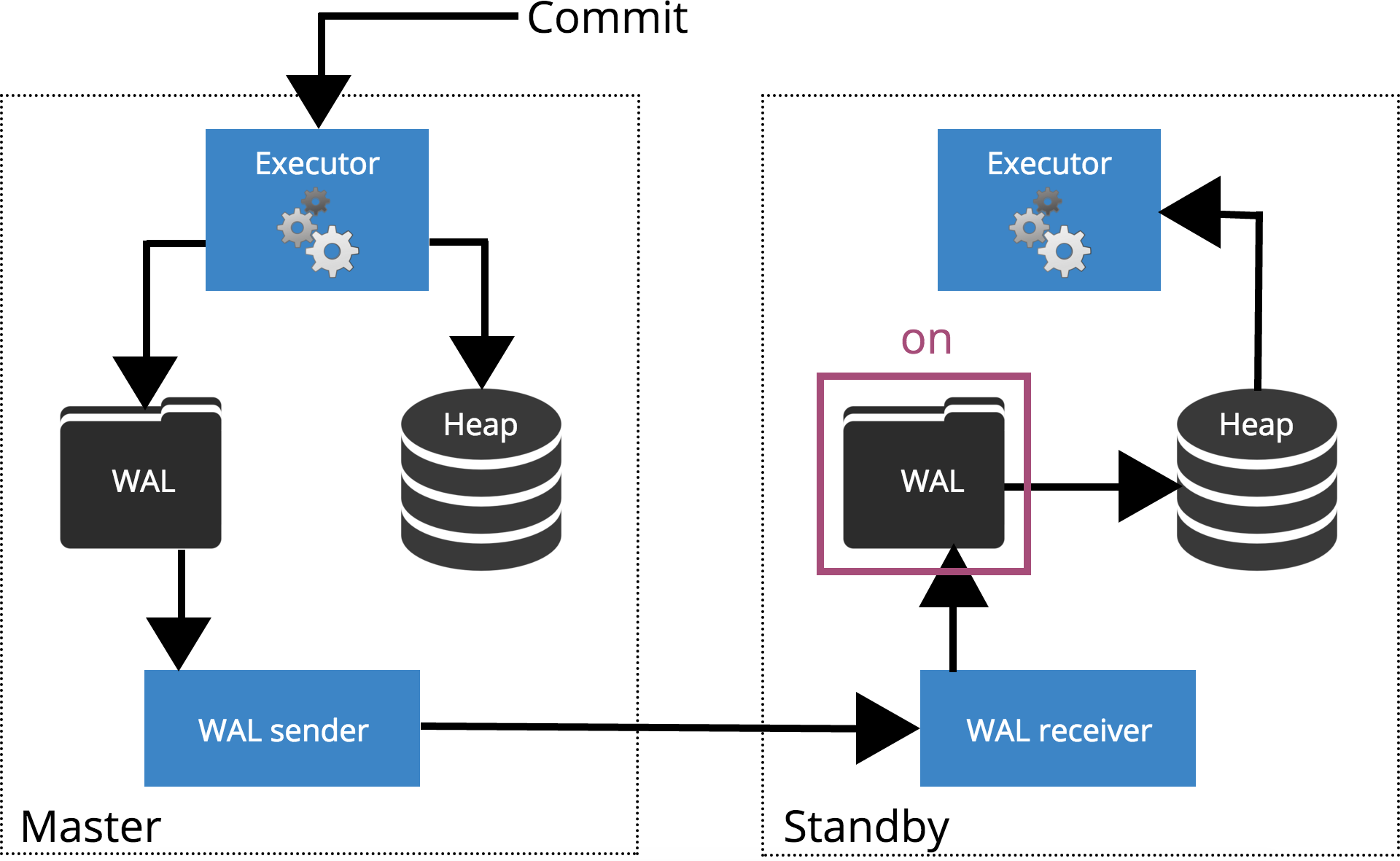

Let’s see how different settings work for different level of synchronisation. Before we start let’s talk how commit is processed by PostgreSQL replication. Client execute queries on the master node, the changes are written to a transaction log (WAL) and copied over network to WAL on the standby node. The recovery process on the standby node then reads the changes from WAL and applies them to the data files just like during crash recovery. If the standby is in hot standby mode, clients may issue read-only queries on the node while this is happening. For more details about how replication works you can check out the replication blog post in this series.

Fig.1 How replication works

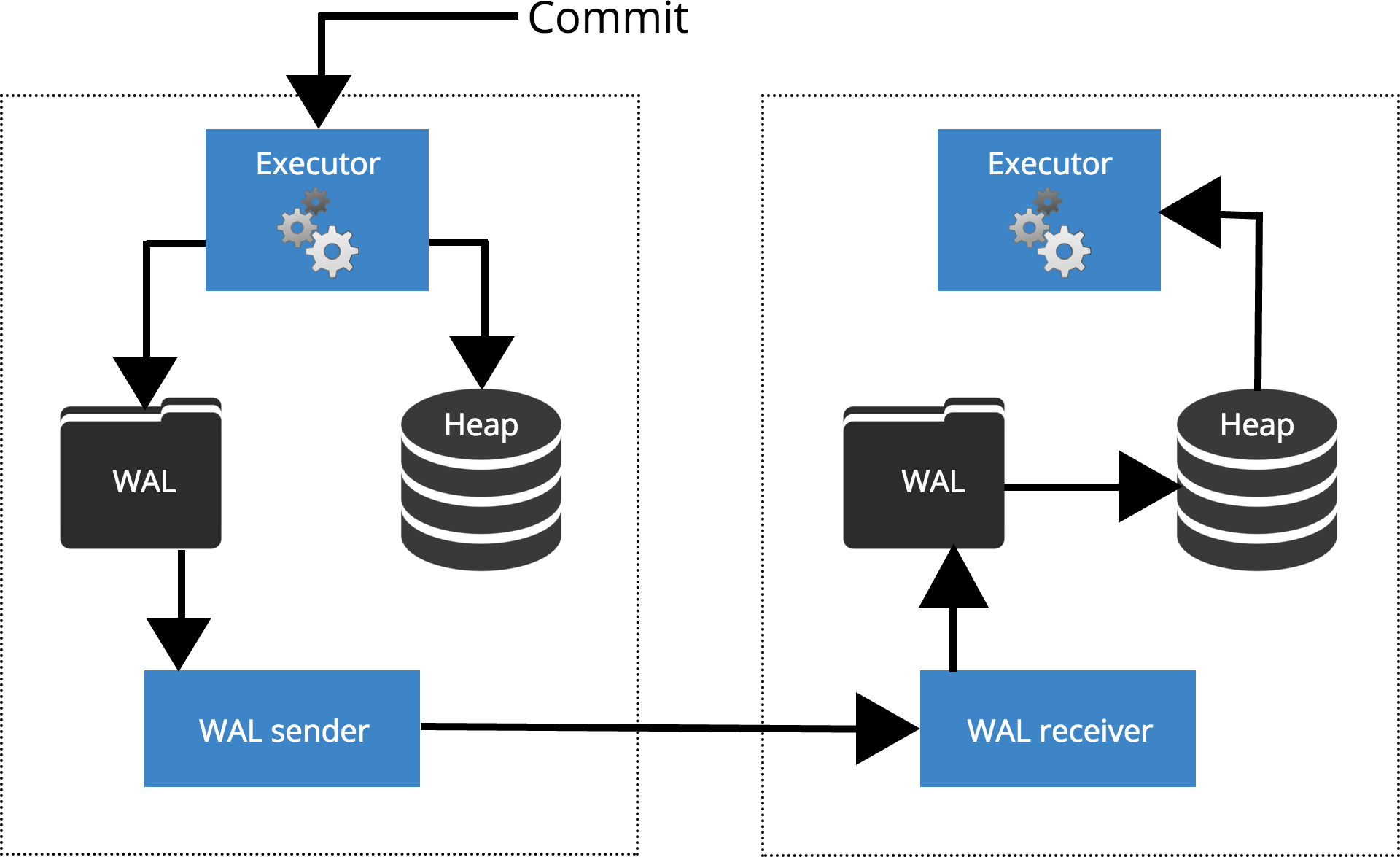

synchronous_commit = off

When we set sychronous_commit = off, the COMMIT does not wait for the transaction record to be flushed to the disk. This is highlighted in Fig.2 below.

Fig.2 synchronous_commit = off

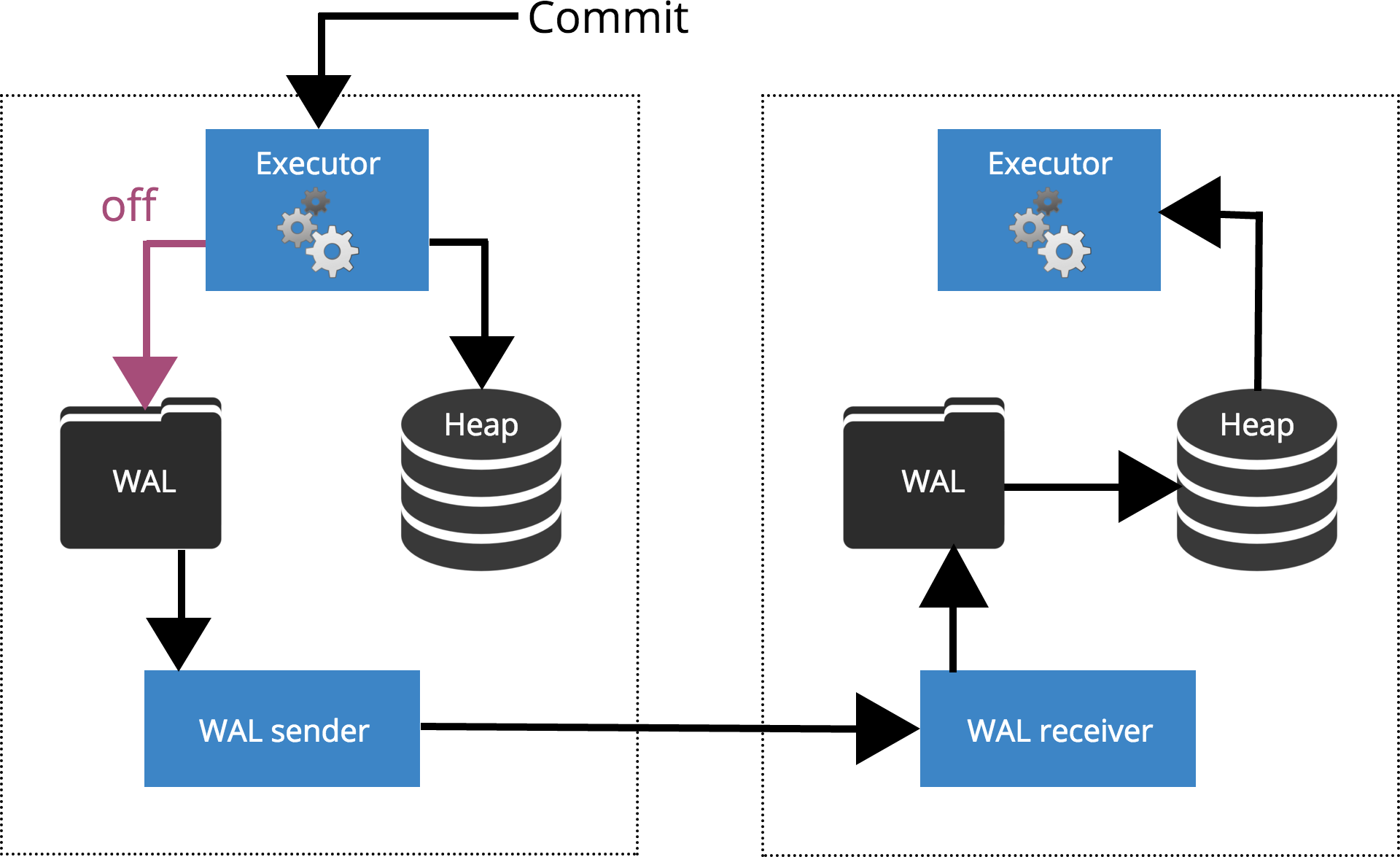

synchronous_commit = local

When we set synchronous_commit = local, the COMMIT waits until the transaction record is flushed to the local disk. This is highlighted in Fig.3 below.

Fig.3 synchronous_commit = local

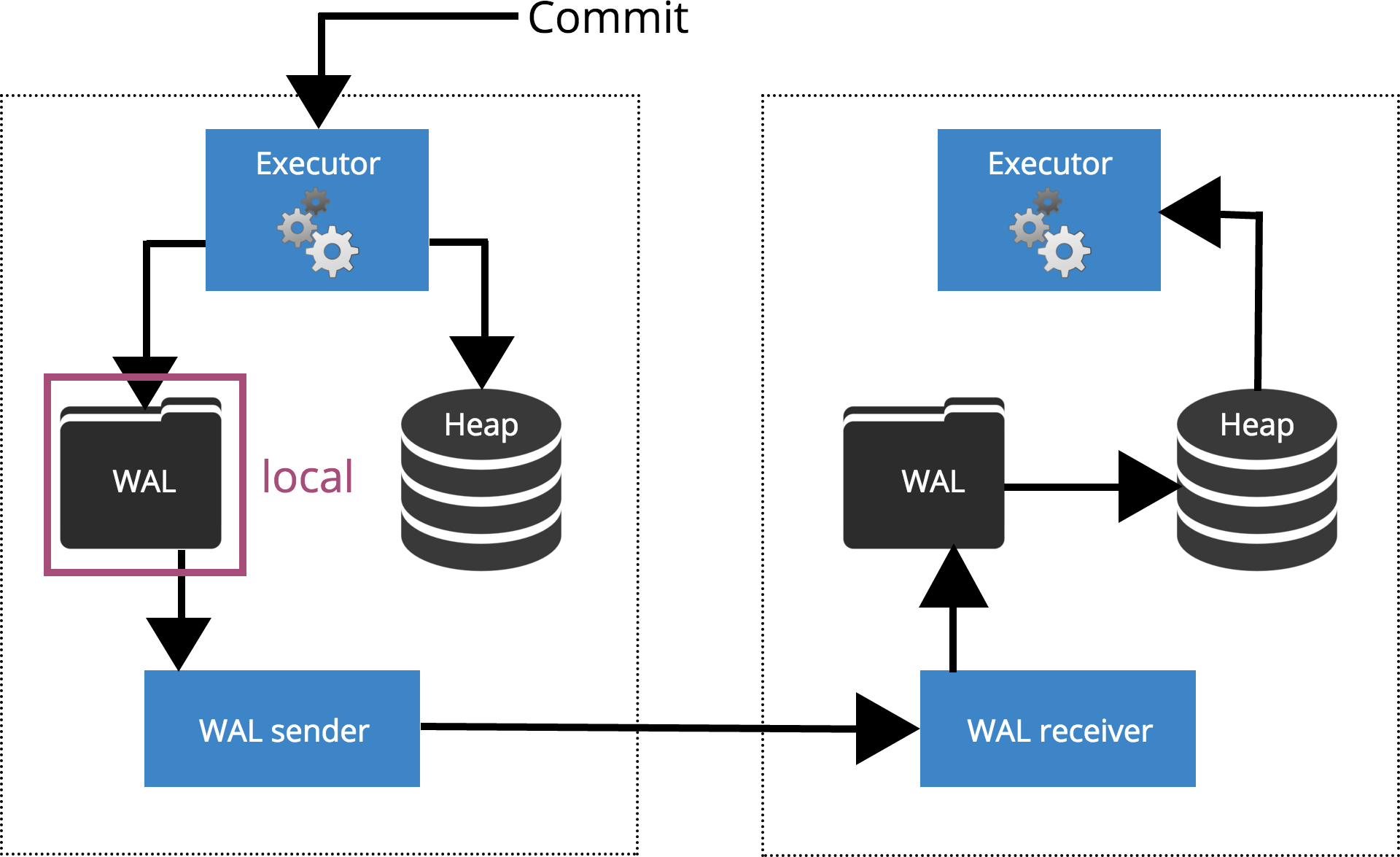

synchronous_commit = on (default)

When we set synchronous_commit = on, the COMMIT will wait until the server(s) specified by synchronous_standby_names confirm that the transaction record was safely written to disk. This is highlighted in Fig.4 below.

Note: When synchronous_standby_names is empty, this setting behaves same as synchronous_commit = local.

Fig.4 synchronous_commit = on

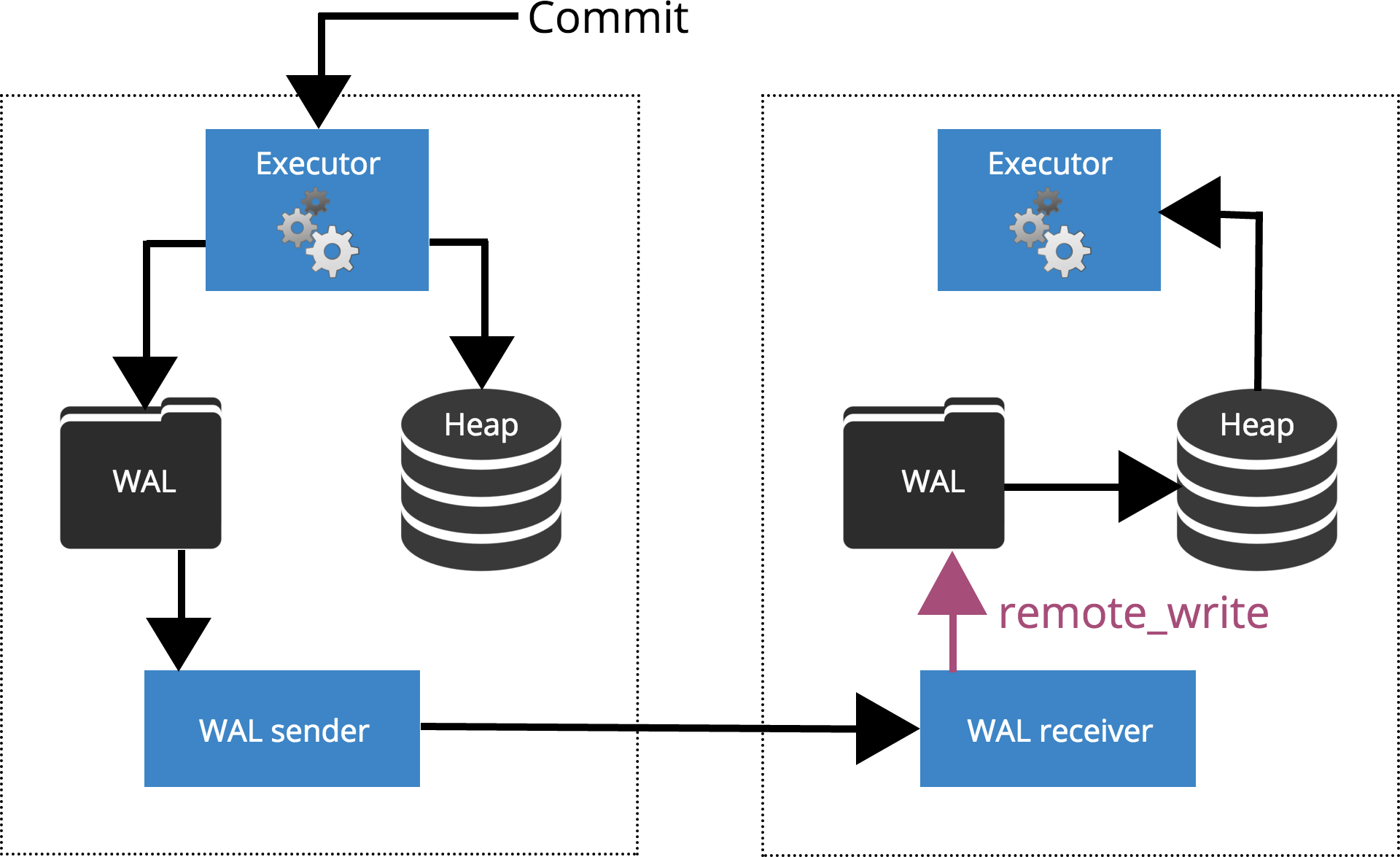

synchronous_commit = remote_write

When we set synchronous_commit = remote_write, the COMMIT will wait until the server(s) specified by synchronous_standby_names confirm write of the transaction record to the operating system but has not necessarily reached the disk. This is highlighted in Fig.5 below.

Fig.5 synchronous_commit = remote_write

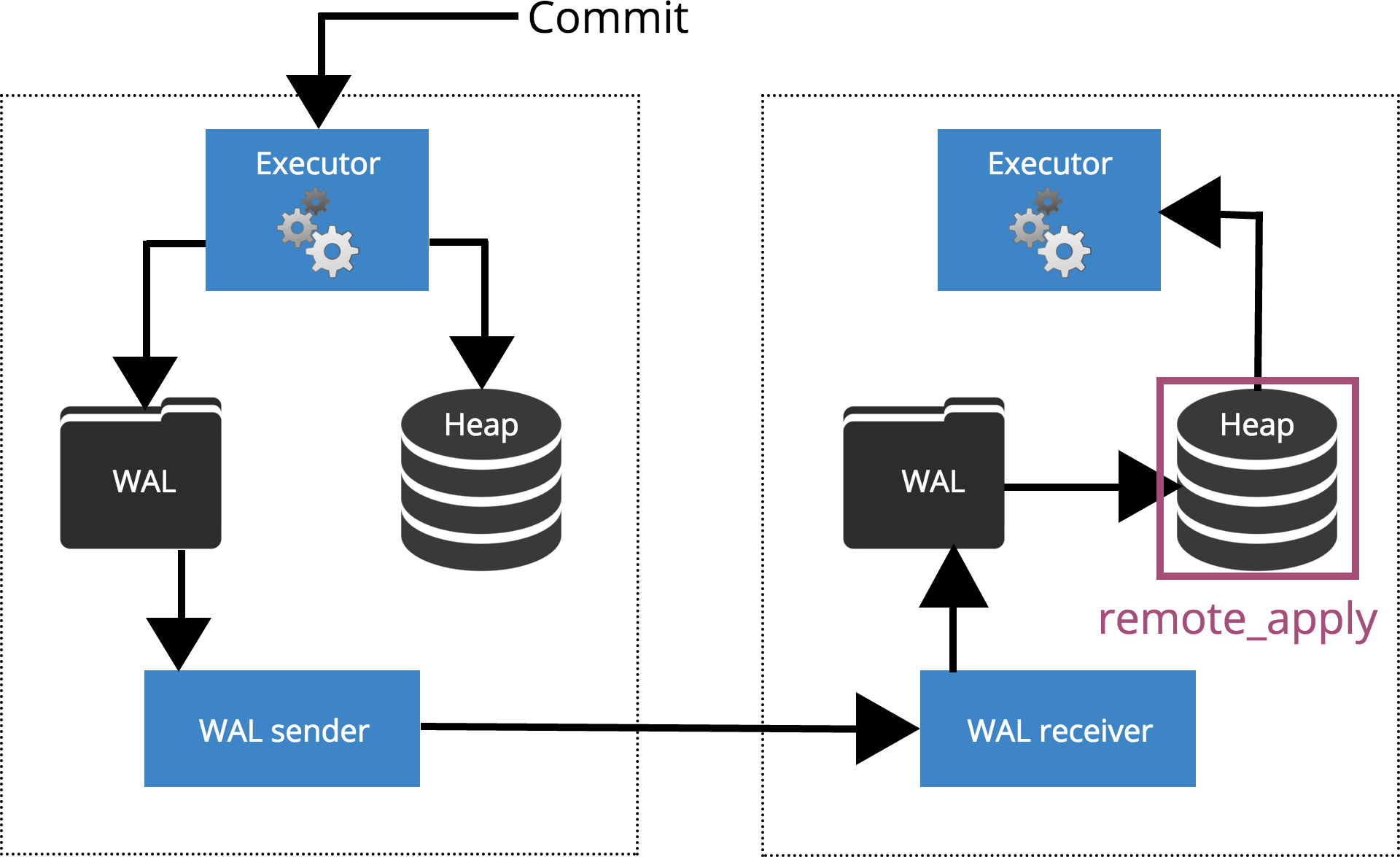

synchronous_commit = remote_apply

When we set synchronous_commit = remote_apply, the COMMIT will wait until the server(s) specified by synchronous_standby_names confirm that the transaction record was applied to the database. This is highlighted in Fig.6 below.

Fig.6 synchronous_commit = remote_apply

Now, let’s look at sychronous_standby_names parameter in details, which is referred above when setting synchronous_commit as on, remote_apply or remote_write.

synchronous_standby_names = ‘standby_name [, …]’

The synchronous commit will wait for reply from one of the standbys listed in the order of priority. This means that if first standby is connected and streaming, the synchronous commit will always wait for reply from it even if the second standby already replied. The special value of * can be used as stanby_name which will match any connected standby.

synchronous_standby_names = ‘num (standby_name [, …])’

The synchronous commit will wait for reply from at least num number of standbys listed in the order of priority. Same rules as above apply. So, for example setting synchronous_standby_names = '2 (*)' will make synchronous commit wait for reply from any 2 standby servers.

synchronous_standby_names is empty

If this parameter is empty as shown it changes behaviour of setting synchronous_commit to on, remote_write or remote_apply to behave same as local (ie, the COMMIT will only wait for flushing to local disk).

Note:

synchronous_commitparameter can be changed at any time; the behaviour for any one transaction is determined by the setting in effect when it commits. It is therefore possible, and useful, to have some transactions commit synchronously and others asynchronously. For example, to make a single multi-statement transaction commit asynchronously when the default is the opposite, issue SET LOCAL synchronous_commit TO OFF within the transaction.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we discussed synchronous replication and described different levels of protection which are available in Postgres. We’ll continue with logical replication in the next blog post.

References

Special thanks to my colleague Petr Jelinek for giving me the idea for illustrations.

PostgreSQL Documentation

PostgreSQL 9 Administration Cookbook – Second Edition