This technical blog explains how CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY (CIC) works and how it manages to avoid locking the table from updates. A unique distinguishing factor of CIC is that it can build a new index on the table, without blocking it from updates/inserts/deletes.

But even before that, let’s understand how Heap-Only-Tuple (HOT) works. It was a landmark feature added in PostgreSQL 8.3 to reduce table bloat and improve performance significantly. But the feature also has some implications on the working of CIC.

Heap-Only-Tuple (HOT)

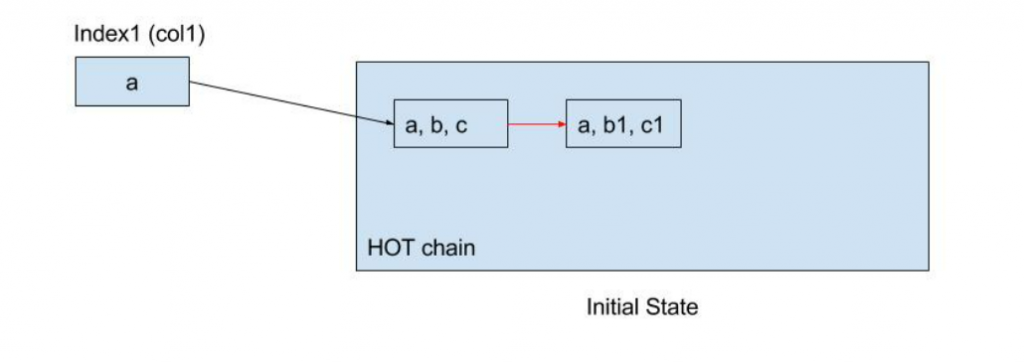

PostgreSQL uses multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) for transactions. In this technique, when a row is updated, a new version of the row is created and the old version is left unchanged. Each version has creator and destroyer information and transaction snapshots are used to decide which version should a transaction see. After some time, the old version becomes dead i.e. not visible to any running or new transactions and hence it can be removed from the table. Earlier each of these row versions were separately indexed, thus causing index bloat. Also unless index pointers are removed, one cannot remove the dead heap tuples, which leads to heap bloat. HOT improved this by requiring that new index entries are created only if a column indexed by one or more indexes is changed. In other words, if an update does not change any of the index columns, the existing index entry is used to find the new version of the row by following the TID chain. This chain of tuples is called HOT chain and a unique property of HOT chain is that all row versions in the chain have the same value for every column used in every index of the table. CIC must ensure that this property is always maintained, when the table is receiving constant updates and we will see in the next section how it achieves that.

In the above example, the table has just one index to begin with. The HOT chain property is satisfied because the only indexed column has the same value ‘a’ in all tuples. Hence we have inserted only one entry in the index and both the versions are reachable from the same index entry.

Create Index Concurrently (CIC)

With that background, let’s see how CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY works, without locking down the table and allowing concurrent updates to the table. Building an index consists of three phases.

Phase 1: At the start of the first phase, the system catalogs are populated with the new index information. This obviously includes information about the columns used by the new index. Yet the index is not allowed to receive any inserts by other transactions at this time. As soon as information about the new index is available in the system catalog and is seen by other backends, they will start honouring the new index and ensure that the HOT chain’s property is preserved. But what happens to transactions which are already in progress? They may not even see the change in catalogs until they receive and process cache invalidation messages. The cache invalidation messages are not processed asynchronously, but only at certain specific points. So CIC must wait for all existing transactions to finish before starting the second phase on index build. This guarantees that no new broken HOT chains are created after the second phase begins.

In our example, we’re building a new index on the second column of the table. In the initial state, the HOT chain is OK with respect to the first index. The existing HOT chain is already broken with respect to the new index and we will see how that is handled.

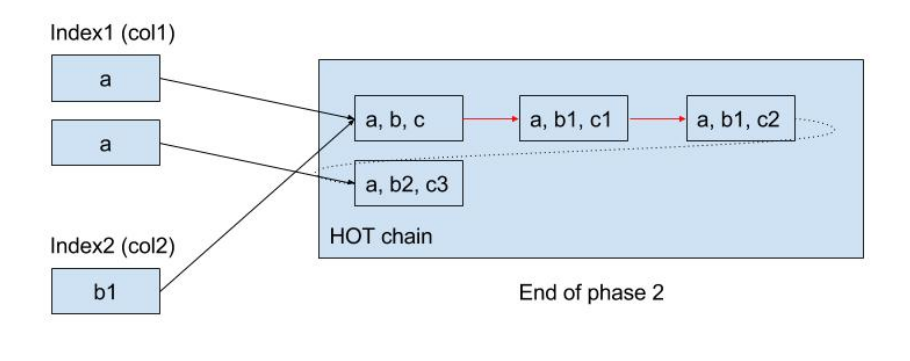

Phase 2: So when the second phase starts, we guarantee that new transactions cannot create more broken HOT chains (i.e. HOT chains which do not satisfy the HOT property) with respect to the old indexes as well as the new index. We now take a new MVCC snapshot and start building the index by indexing every visible row in the table. While indexing we use the column value from the visible version and TID of the root of the HOT chain. Since all subsequent updates are guaranteed to see the new index, the HOT property is maintained beyond the version that we are indexing in the second phase. That means if a row is HOT updated, the new version will be reachable from the index entry just added (remember we indexed the root of the HOT chain).

In our example, when we start building the new index, we index the version (a, b1, c1) since that’s the version visible to our transaction.

During the second phase, if some other transaction updates the row such that neither the first not the second column is changed, a HOT update is possible. On the other hand, if the update changes the second column (or any other index column for that matter), then a non-HOT update is performed. A new index entry is now added to the existing index, but since the new index is not yet open for inserts, it does not see the new value ‘b2’.

So at the end of the second phase, we now have ‘b1’ in the new index, but version with ‘b2’ is not reachable from the new index since there is no entry for ‘b2’. Also, new HOT chains are created or extended only when HOT property is satisfied with respect to both the indexes. So when ‘b1’ is updated to ‘b2’, a non-HOT update is performed.

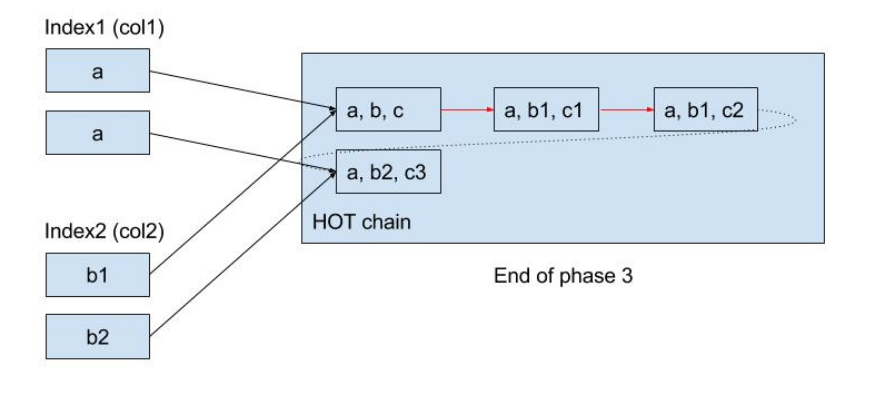

What happens to existing HOT chains though? After all they could be broken with respect to the new index since this index did not exist when the chain was created. So if an old transaction tries to use the new index, it might get wrong results. This is handled at the end of the third phase (see below).

Once the index is built, we update the catalogs and make sure that the index is now available for inserts. Once the catalogs are updated and cache invalidation messages are processed by other processes, any transaction that does a non-HOT update or inserts a new row, will maintain the index. Like the phase 1, we once again wait for all existing transactions to finish to ensure that every new transaction now has latest catalog information.

Phase 3: You must have realised that while second phase was running, there could be transactions inserting new rows in the table or updating existing rows in a non-HOT manner. Since the index was not open for insertion during phase 2, it will be missing entries for all these new rows. In our example, version (a, b2, c3) does not have any appropriate index entry in the new index. This is fixed by taking a new MVCC snapshot and doing another pass over the table. During this pass, we index all rows which are visible to the new snapshot, but are not already in the index. Since the index is now actively maintained by other transactions, we only need to take care of the rows missed during the second phase.

The index is fully ready when the third pass finishes. It’s now being actively maintained by all other backends, following usual HOT rules. But the problem with old transactions, which could see rows which are neither indexed in the second or the third phase, remains. After all, their snapshots could see rows older than what our snapshots used for building the index could see. For example, if there exists a transaction which can see (a, b, c), the new index cannot find that version since there is no entry for ‘b’ in the new index. The new index is not usable for such old transactions. CIC deals with the problem by waiting for all such old transactions to finish before marking the index ready for queries. Remember that the index was marked for insertion at the end of the second phase, but it becomes usable for reads only after the third phase finishes and all old transactions are gone.

Once all old transactions are gone, the index becomes fully usable by all future transactions. The catalogs are once again updated with the new information and cache invalidation messages are sent to other processes.

An index built this way does not require any strong lock on the table. Not even a lock that can block concurrent inserts/updates/deletes on the table. And that’s why people love to use CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY on a system with high write rates.